Curtis Lawrence '80 on the night he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Chicago Journalism Association. Photo credit: Judy Fidkowski

They trusted him with their stories

Curtis Lawrence '80 had his own pathway to Augustana College from Chicago’s South Side.

The honored Chicago journalist, who just retired, got a push toward Rock Island from his pastor at Salem Lutheran Church, one of the oldest churches in Chicago and one of the first on the South Side to welcome Black families like Lawrence’s starting in 1949.

His father had told him "Don't even think about going to college outside Illinois." So, armed with a letter of recommendation from his pastor, Karl J. Mattson '55, Lawrence moved Augustana to the top of his list of college choices.

Lawrence had visited the campus while in high school, but he wasn't sold.

"I remember thinking I would never go there. All those hills, you know, just too much walking to get places," said Lawrence, with an easy laugh. "So, of course, I ended up going there."

That decision led to a 44-year career in journalism at six daily newspapers in the Midwest, including the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Tribune. He mentored many young journalists as a professor at Columbia College for 20 years, and at the non-profit news organization Block Club Chicago, where he recently retired as senior editor of investigations.

(Left to right) Manny Ramos, Mick Dumke, Rachel Hinton, Curtis Lawrence and Mina Bloom — the reporters and editors on Block Club Chicago’s investigative team, The Watch.

Photo credit: Colin Boyle/ Block Club Chicago

Already a winner of the prestigious Studs Terkel Award, Lawrence received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Chicago Journalism Association on November 15.

But back to the beginning. How was the transition from the South Side to Augustana, still a predominantly white college in 1976?

The Black students probably did feel a little isolated, he said, but they supported each other.

"We would do our own dances," he said. "We would tutor each other. We adopted little brothers and little sisters when they came in. So we took care of each other."

The Black Student Union raised the money to bring Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis to campus in 1978, and also staged "Purlie Victorious," a comedy written by Davis.

"Ruby Dee kissed me on my cheek," he said, grinning.

And there were faculty members who offered extra support and guidance.

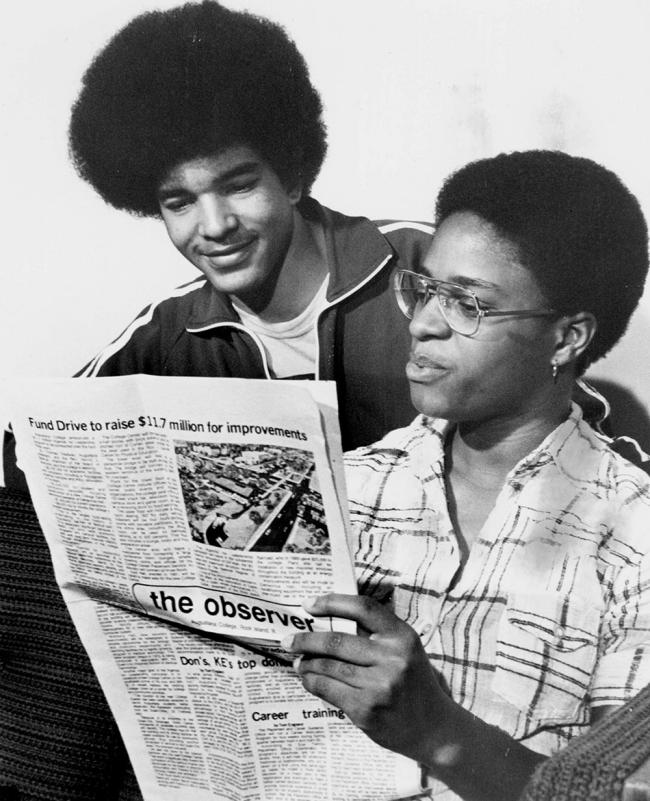

Curtis Lawrence ’80 and Wynetta Newman ’80 from the November 1977 issue of the Augustana College Bulletin.

Photo credit: Augustana Special Collections

"At the time there was one Black professor, John Hildreth in the music department, God bless him, who kind of uncled and fathered us," Lawrence said.

He said that later, after becoming a professor himself, he realized just how much Dr. Hildreth had his hands full, teaching and mentoring dozens of Black students who looked up to him.

Other mentors were Dr. Charlene Hawks, who taught in the English department and also ran the reading lab where she tutored many students, and Dr. Nancy Huse, his advisor.

But it was Dr. Harold Bell in the political science department who really changed the course of Lawrence’s path. Dr. Bell founded the Black Culture House and brought the Rev. Jesse Jackson to speak at a Black Power symposium in 1969.

A friend told Lawrence that Dr. Bell was looking for a Black student to apply for a newspaper internship. So Lawrence, an English major who liked writing, decided to go for it.

"So my senior year, I had an internship at the Rock Island Argus and after I graduated, they hired me full time," Lawrence said. "I was probably one of the first Black full-time journalists there. And I stayed there for about two years. And that puts me into journalism."

In those two years Lawrence wrote a lot, covered a variety of people and events, and laid out pages.

"It was great," he said. "I mean, I learned more there. The thing about working at a paper like that is, you did everything."

There were some stories that stick in his memory, like the assignment to do a "man on the street" asking people if they thought Martin Luther King Day should be a federal holiday. (Lawrence laughs several times while telling this story.)

"And so I was out with the photographer and these guys were coming out of a bar and I asked them and they just went ballistic. Not violent, but just screaming. Like, 'What the hell do you think? No, we don’t think it should be a holiday.'

"I later looked back and thought: What was on my mind approaching these guys coming out of a bar asking them this?!"

"I covered education in Milwaukee, tornadoes in Minnesota and public housing in Chicago. In all those places, I found people willing to trust me with their stories, often at traumatic times in their lives."

After the Argus, Lawrence returned to the Chicago area for graduate school at Northwestern University’s Medill School, followed by a couple of years at the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

"And then I kind of dropped out of journalism for a minute," he said. "I was in my 'find myself' period."

He went to San Francisco and worked for the non-profit Food First, returned to Chicago and taught at a Catholic high school, and then was hired by Chicago Alderman Tim Evans, floor leader for then-Mayor Harold Washington.

But after the death of Mayor Washington, the job was gone overnight. He decided "maybe journalism isn’t so bad."

And so the Lifetime Achievement award is for his body of work at large dailies in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Chicago and Milwaukee over decades. But although he appreciates the award, Lawrence downplays his career a bit.

"Especially like at the Sun Times and papers like that, when things were rough, even if you had a beat, you were also a general assignment report," he said. "You just did everything. I never had a big beat for a long time. I wasn’t a columnist. I just saw myself as kind of a scrub doing the daily stuff."

However, that “daily stuff,” such as his reporting on public housing for the Sun Times, brought him the Studs Terkel Award. These are given for a body of work showing excellence in covering and reflecting Chicago's diverse communities. The list of winners is a "who’s who" of Chicago journalism.

Terkel was a writer, historian, actor and broadcaster who won the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction in 1985. He is remembered for his oral histories of common Americans, and for his radio show in Chicago.

Curtis Lawrence with his Lifetime Achievement Award. Photo credit: Judy Fidkowski

"You know, we always say we don’t want awards, but that was an award I did want because my high school history teacher is mentioned in several Studs Terkel books," Lawrence said. "So I always held Studs Terkel on an elevated platform."

Despite the large changes in the newspaper industry, Lawrence said he is optimistic for the future of non-profit models like Block Club Chicago that are funded by grants and subscriptions. Block Club Chicago, which is dedicated to delivering reliable, nonpartisan and essential coverage of Chicago’s diverse neighborhoods, is looked at as a national model, he said.

Lawrence was the senior editor of investigations at Block Club Chicago. In his retirement letter to the staff, Lawrence claimed he was never a superstar in the newsroom.

"But I had many good stories," he said. "I covered education in Milwaukee, tornadoes in Minnesota and public housing in Chicago. In all those places, I found people willing to trust me with their stories, often at traumatic times in their lives."

Now, in retirement, Lawrence said he feels like an "older version of finding myself."

"I haven't been back to the Quad Cities in awhile, but I do get moments where I miss Augustana," Lawrence said. "I have many memories of the Black House on the hill, which was a meeting and a place of bonding and community for the Black students. I miss tracking up and down the Slough as a shortcut from the Erickson dorm to the main campus. And sometimes the Slough was good just for walking and getting my head in gear."

One of the buildings he remembers fondly is East Hall, where many of his English literature classes were held and where "the beloved Charlene 'Char' Hawks ran the Reading and Writing Lab."

One of his favorite books — a battered paperback that is barely holding together — is "Winesburg, Ohio" by Sherwood Anderson. He was introduced to it by Dale Huse, who taught Midwestern literature at Augustana.

Lawrence has written a play which has had a couple of readings that he would like to see staged. He wants to work on writing fiction.

"One of my goals," he said, "is to have something published and one day go to the Augustana library and see something that I wrote there."