Augustana and the civil rights movement

(This story was written in celebration of Augustana's sesquicentennial in 2010.)

Black students, college had different perceptions on the pace of progress

Although the first African-American student graduated from Augustana in 1929, the student body as a whole remained overwhelmingly white and, largely, disinclined to political action at the start of the Civil Rights movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Civil rights activities in other parts of the country received notice on campus but did not initially inspire active response, either on behalf of the larger movement or in support of greater equality "at home."

Augustana's participation in the nationwide "Fast for Freedom Food" of 1964 constituted the first significant campus effort in recognition of civil rights concerns. The fast was organized by the United States National Student Association, an organization known for its liberal views and commitment to social justice. Students at colleges and universities — including 416 at Augustana — agreed not to eat dinner for one evening; the value of the uneaten food went to poor African-Americans in the South.

The Freedom Fast succeeded in raising awareness and promoting student engagement with issues of civil rights through economic justice. As Augustana President C. W. Sorensen told the Observer, the event "(gave) the students a chance to DO something, rather than act as bystanders."

Afro-American Society

The Freedom Fast was ultimately an expression of empathy for the beneficiaries of the fast, not an attempt to change conditions for minority students at Augustana. More vigorous on-campus efforts in support of civil rights only began later in the 1960s and 1970s.

These efforts came largely at the instigation of Augustana's small population of black students, who formed the Afro-American Society (AAS) in spring of 1968. The AAS constitution opened with the society's intent to "give outward expression to the common, inward feelings of brotherhood, love and pride which unite us" and went on to list its purposes, which included developing the sense of solidarity among black students on campus as well as improving relationships between African-Americans and the rest of the Augustana community.

Soon, the AAS began to conduct talks with Augustana's administration, pushing for a full-time black faculty member; black counseling and admissions staff; better recruitment of black students, followed by better orientation services when those students enrolled; and increased attention to black history and culture in the Augustana curriculum.

Black Power Symposium

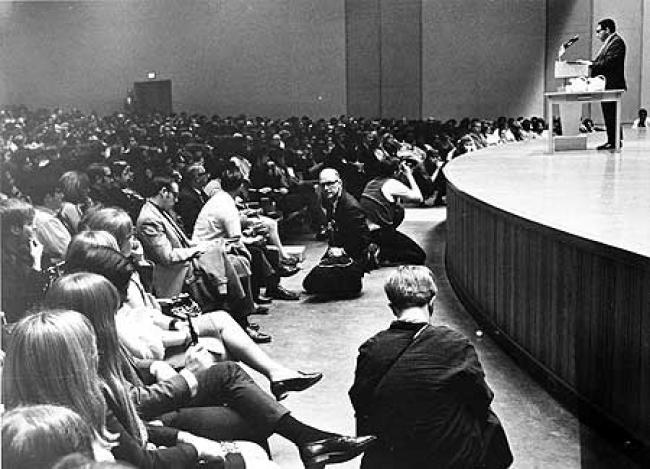

Among the Afro-American Society's first highly visible accomplishments was organizing the Black Power Symposium of February 1969. Black Power, a movement that sought self-determination and political efficacy for African-Americans through prizing black culture and community, was viewed with fear and suspicion by many whites in the 1960s. At Augustana, a number of alumni, parents, and members of the surrounding community expressed concern that the college's very agreement to hold the symposium was a sign not only of its endorsement of Black Power but also of a change in its fundamental character.

Such responses prompted President Sorensen to hold a press conference at which he read a statement in support of the symposium. Organizing such an event did not imply official approval of the views expressed, he argued. Rather, students have the right to free inquiry about pressing questions and the obligation to investigate those questions responsibly.

"What is the purpose of this symposium, as the students see it?" he asked. "Probably, it is something like this. The students sense the urgent importance of the topic, Black Power. They wish to see, in person, some of the key personalities in that field. They want to hear what these men have to say. And then, independently, the students will have their own opinions about things."

The symposium itself proved popular and drew large audiences: the first evening, in Centennial Hall, saw an attendance of more than 2,000, including hundreds of students from other colleges and universities in Illinois and surrounding states. Over the course of the weekend, Dick Gregory, Andrew Hatcher, Roy Innis, Jesse Jackson, Roy Morrison, and C. S. Smith spoke about the political, economic, and social situation of African-Americans.

Sit-in at the president's office

As important an achievement as the Black Power Symposium was for the fledgling Afro-American Society, it was not immediately attended by equally great strides in the situation of black students on campus. The AAS did argue successfully for a Black Culture House, which the college officially established in 1970. But racial inequalities persisted on campus.

In an essay for the AAS orientation booklet of 1969-1970, AAS president Kenneth Mason not only shared the goals of the AAS and pointed out the success of the recent Black Power Symposium, but also included a word of caution: "You must remember," he told the incoming black students of 1969, "that Augustana is a small college, Rock Island a small city, and our Afro-American Society even smaller... If you're looking for a good thing in a small package, if you can accept a challenge and not be easily discouraged, then I say to you come and ‘Check us out,' because you're just what we need."

What remained to "discourage" black students at Augustana? Put simply, many felt that racial inequalities, even discrimination, remained unaddressed at an institutional level; these students desired a firm campus-wide policy on race and racism, a policy arising from the highest levels of college governance. In fact, President Sorensen began preparing a statement on racism in 1971, and he sought its approval by the Board of Trustees.

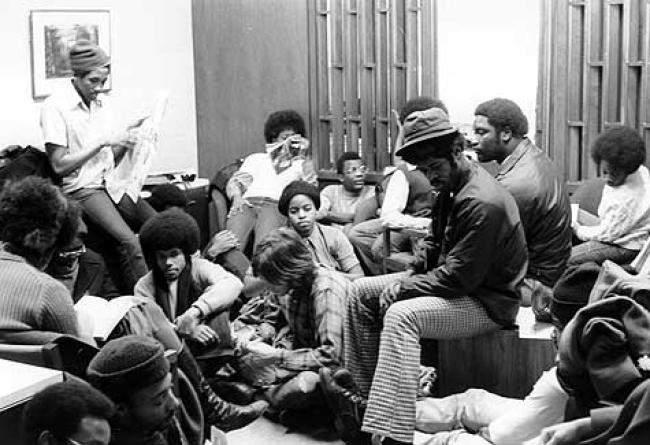

But the college's progress was not fast enough for the Black Student Union (or BSU: the new name for the Afro-American Society). In February 1972, a number of black students held a sit-in in President Sorensen's office. The occasion was a meeting between Sorensen and three BSU leaders, who demanded the college release an official written statement on racism and how racist actions should be addressed on campus. More than 30 of Augustana's 54 black students waited in the outer room of Sorensen's office as the three student leaders made their case.

The college had been stalling the BSU in its request for an official statement since May 1971, the students claimed. Although Sorensen had recently attempted to address the question by issuing his own, personal statement on racism, the students argued that his effort fell short: the BSU had not been consulted on Sorensen's statement, which was not specific enough about how the college would address racist actions.

This meeting and its attendant sit-in made the local newspapers, and it resulted in another meeting between Sorensen and the BSU, in conjunction with Augustana's Human Relations Committee, the next week. The parties to that meeting wrote and issued a new statement, which promised expulsion from the Augustana community of anyone found guilty, after due process, of racist actions. "Due process" would be determined by the Human Relations Committee, which represented students, faculty, and administration and included six African-Americans among its 14 total members. The committee would investigate any infractions and make a recommendation for action to the college president, who would reply to that recommendation within one month.

Different views and perceptions

The new statement met the demands that the Black Student Union had brought to its sit-in. Further assessments of civil rights on the Augustana campus varied, however.

In April 1972, for example, Augustana junior Joe Looney (one of the three BSU members who had met with President Sorensen during the sit-in) wrote a lengthy editorial-type piece for the Observer, arguing that racism remained a major concern on campus. Black students, he contended, continued to experience distrust, suspicion, and overtly racist actions at the hands of faculty and fellow students.

The Rock Island Argus, on the other hand, in an editorial responding to Augustana's new official statement on racism, argued that the BSU's concerns were understandable given the country's history, but their demands of the college had been "overzealous." Augustana's "record in this respect (i.e., its treatment of race and race relations) has been exemplary," the editors wrote.

Such disparate assessments as those offered by Looney and the Argus' editorial board point not only to the potential for divergence among perspectives on and off campus, but also to the effects of increased diversity at a small school historically associated with white Protestants of European descent. Indeed, the new official statement on race and racism did not make the on-campus situation perfect in the eyes of most African-American students at Augustana. Led by the BSU, they continued their efforts toward racial equality throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Because institution-level efforts to address racism cannot account for the perspective of each individual on campus, incidents of racism or, perhaps more frequently, insensitivity, did not disappear overnight. However, BSU members and others in the Augustana community acknowledged over time the substantial progress that had been made since the founding of the Afro-American Society.

Today, that progress continues, albeit with vastly different motivations and aims than those that inspired the Afro-American Society beginning in the 1960s. Augustana's population remains majority white, Christian, and Midwestern, but it actively recruits students from outside those demographics in an attempt to increase all forms of diversity on campus.

Support systems for students who might in the past have felt outnumbered on campus have strengthened substantially, providing the groundwork for an increasingly diverse campus environment. Curricular changes — developed over the past decades — provide all Augustana students with expanded opportunities to study diversity and global concerns. In such efforts toward an Augustana education that both reflects and illuminates ongoing changes in United States society and culture, the college continues with projects championed by earlier students who sought to bring home the promise of the civil rights movement.

— Stefanie R. Bluemle

Reference Librarian