Memories of the Manhattan Project

(From the Summer 1999 edition of Augustana magazine, reprinted in celebration of Augustana's sesquicentennial in 2010.)

From Augustana magazine, Summer 1999

In the early 1940s, Germany banned the export of uranium, and the United States feared German scientists were developing a nuclear weapon. In response, the government organized the Manhattan Project (1942-1946) to produce two types of atomic weapons, a uranium bomb and a plutonium bomb.

The Project took place at three large secret sites: Oak Ridge, Tenn.; Los Alamos, N.M.; and Hanford, Wash., and dozens of smaller sites. These installations, many of them hidden in mountains and mesas, became tightly guarded communities in the government's effort to develop and produce the most dangerous weapon in the history of the world. Although as many as 125,000 people were employed at one time, and hundreds of thousands during the run of the Project, the work was conducted in secrecy from the enemy as well as the American public.

In recognition of the World War II-Era Classes Reunion in May 1999, here are six condensed essays by or about Augustana graduates whose contributions were significant to the success of the Manhattan Project and to the end of WWII.

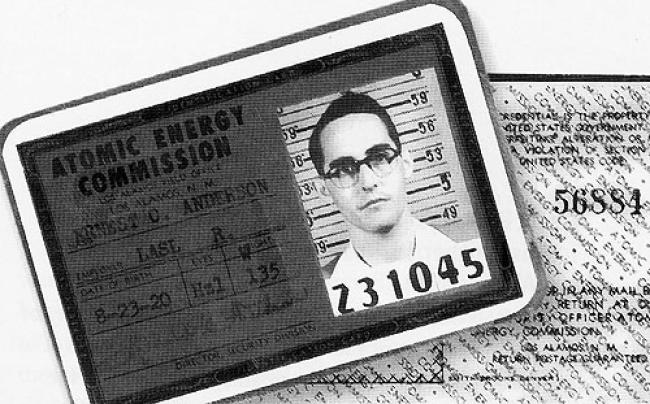

By Dr. Ernie Anderson '42, Los Alamos, N.M.

In the winter of 1941-42, John Wertz, an assistant of Augustana chemistry professor Dr. J.P. Magnusson, was taking courses at the University of Chicago. He came back with word that a war project was looking for chemists. I had decided to go to Iowa City in the fall; the university had a fair chemistry department but a superb orchestra.

So I went to the Metallurgical Lab at Chicago looking for a summer job. Fortunately, I had taken an extension course at St. Ambrose College on the chemistry of powder and explosives. The interview was very low key. I wasn't the analytical chemist they had in mind. I explained I wasn't enthusiastic either because I was going to study organic chemistry at Iowa. But could I have a job for the summer? They said duration was no problem to them. (They knew very well that once I found out what was up, I would never leave.) The problem was they needed people yesterday. How soon could I come? It was February and I was going to graduate in June. Augie was patriotic and willing so I took an informal philosophy exam and skipped the rest for a degree in absentia in June.

At the Metallurgical Lab, we knew about nuclear energy and theoretical chain reactions; bombs weren't talked about. So we chemists prepared ever-purer uranium and analyzed it for minute traces of the exotic elements that had excessive appetites for the precious neutrons. The physicists made their measurements and computed the "pile" which Dr. Enrico Fermi built in the famous squash court in the west stands of the abandoned athletic field. In addition to our full-time jobs, we were permitted (indeed, expected) to take the courses leading to Ph.D. research.

After two years on the Midway campus, our group began to disperse to mysterious places known prosaically as sites X, Y and Z. We analyzed water from these places and immediately went to the literature to determine where in the United States such water was found. More clever people at other labs looked into their libraries' state guide books and found that many of their missing colleagues shared ties to Tennessee and New Mexico. I was by then a supposed expert in determining miniscule amounts of boron in minute samples of uranium, so I was offered a chance to go to Site Y "somewhere in northern New Mexico."

Then things became very hush-hush. Do not close your bank account; continue to use it. Have all your journals and other subscriptions sent to an address in Los Angeles. Your address (family only) is P.O. Box 1663, Santa Fe, N.M. No visitors are allowed closer than Albuquerque, about 80 miles away, except those with clearance through Army intelligence.

The birth certificate of my second son states his place of birth as P.O. Box 1663, and my New Mexico driver's license is in the name of No. xxxx, Special List B, signature not required.

The deal that Project Director Dr. Robert J. Oppenheimer ("Oppie") had made with U.S. Army General Leslie Groves was that in exchange for tight military security (including mail censorship whose existence was censored) and limits on travel, the lab would have no compartmentalization internally. Every Tuesday night, one of the two theaters was reserved for a colloquium of the entire scientific staff. There were only two forbidden topics: the rates of delivery of uranium and plutonium to us and the date we would deliver a weapon. Oppie's idea was not only to keep up morale but also to take advantage of everyone's ideas and suggestions. So early on we watched Dr. Edward Teller draw fantastically improbable diagrams of his idealized, theoretical hydrogen bomb.

The Tuesday night colloquia sometimes featured a committee on the stage for a roundtable of a current problem. One night I counted four Nobelists on the stage with two more in the audience, not counting several who later received the honor.

In the spring of 1946 my family returned to Chicago so I could resume the quest for a Ph.D. It turned into a frightful trial because of housing problems which Bob Fryxell '44 shared with us in part. I was fortunate to be able to work with Dr. Willard Libby in the discovery of natural radiocarbon and the development of a method of accurately dating archaeological artifacts. He got the Nobel Prize and I got my degree, which I considered a fair division of the rewards.

In 1949 we hurried back to the haven of Los Alamos and stayed there some 30 years until my retirement in 1979. This time I chose to join the biomedical research group studying the health hazards associated with nuclear energy...a chemist doing physics for a bunch of biologists. This was the same group Fryxell had worked for during the war but its field had expanded to include the effects of irradiation from external sources. During the years, the focus shifted to the study of world-wide fallout from nuclear weapons testing, where my experience in the measurement of very low levels of radioactivity was useful.

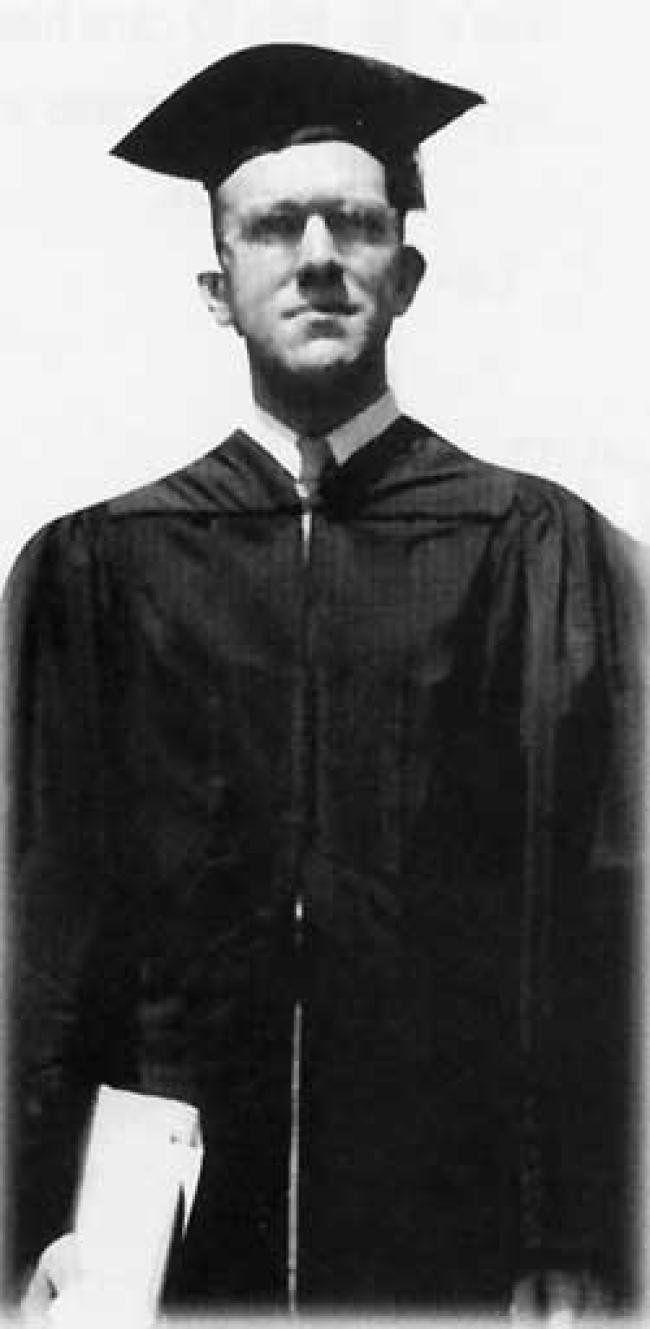

By Dr. Paul Fryxell '49 for his brother, Dr. Robert Fryxell '44, Los Alamos, N.M.

When Bob was still at Augie, he went to the University of Chicago to be part of the Manhattan Project because of his much-needed expertise as an analytical chemist. He finished at Augie later, in 1944. He was at Chicago for a year or so before he was transferred to Los Alamos "for the duration," although at the time we did not know where he was. He had an APO number, and we received censored mail from him. Only after the bombing at Hiroshima did we learn where Bob had been and what he had been doing.

Bob's expertise was in analytical chemistry. At Los Alamos, he was in the medical physiology research group researching the metabolism of plutonium, of which they knew virtually nothing at the time. He was responsible for tracking trace amounts of plutonium and uranium in laboratory animals.

They were quite isolated at Los Alamos and sought various forms of recreation, including hiking and music, both of which Bob enjoyed. In fact, Bob was one of the prime movers in the beginning of music activities in wartime Los Alamos. A fine cellist, he participated in many recitals and was responsible for organizing chamber music evenings involving the musical people stationed there. He played with accomplished pianist Dr. Edward Teller, often referred to as "the father of the H-bomb," nearly 20 times during a period of a year and a half, usually in their homes.

Bob returned to the University of Chicago after the war to complete his doctorate in physical chemistry. For the rest of his career, he ran a research laboratory for General Electric, first in Pittsfield, Mass., later in Cincinnati. He died in 1987.

By Dr. Cecil Nelson '44, Oak Ridge, Tenn.

During my three years at Augie, I took most of the math and physics courses offered. I only needed physical chemistry in my senior year to complete a double major in chemistry and physics. Since it was wartime and I was deferred to complete my bachelor's in chemistry, I decided to finish at the University of Chicago where I could continue with graduate courses in chemistry. I roomed with Bob Fryxell '44 and Ernie Anderson '42 during that year at Chicago, and that's when I heard about the Manhattan Project. Bob was involved with it while taking courses at Chicago.

This appealed to me because it would mean I could continue being deferred while doing scientific research on the Project. After applying for a job in February 1944, I finished my degree at Chicago, left before graduation exercises and arrived in Oak Ridge, Tenn., on March 20, 1944.

During the war, I first did chemical research on plutonium isotopes. I turned down the opportunity to go to Hanford, Wash., as a group leader to analyze plutonium samples. Instead, I began doing analytical chemistry research on the fission isotopes while at Oak Ridge, and continued with this until the war was over.

I don't remember many anecdotes during those years at Oak Ridge except that we were very busy. We lived in dormitories because we were unmarried and rode free buses (like school buses). Married people had housing based on number of children and ranking of importance. In the spring of 1944, I lived in a section where dormitories were being built as fast as possible even if it rained and was muddy.

Every day, we all got up early to go to the cafeteria and to our buses. Once someone left his car parked at the end of the boardwalk overnight. The next morning people opened the car's doors and climbed through the car to avoid going through the deep mud. Mud was the fact of life during the spring of 1944 due to the amount of construction going on.

People always speculated about what was being produced at Oak Ridge because only top officials and scientists directly involved in the Project knew for sure. Many trucks would bring materials into "the reservation," but no one saw anything leave. Everyone needed some sort of security clearance to go anywhere. Cars entering and leaving the reservation were searched, and we all needed badges to enter the gates.

There were three large laboratories, called X-10, Y-12 and K-25, each with a different goal. Clair Schersten '39 and I worked at X-10 where the goal was to build a prototype nuclear reactor to produce plutonium (used in the second atomic bomb). Others, including my future wife, Roberta Carmichael, worked at Y-12 where the goal was to separate the fissionable uranium isotope (used in the first bomb) from the rest by using very large magnets. Many others worked at K-25 where the goal was uranium-235 separation using gaseous diffusion. Some said the main production building at K-25 was so large that workers wore roller skates to move around inside the building.

When we went to our labs at X-10, we were issued radiation film badges plus radiation gauges to read the amount of radiation we had received. We left these badges at the gate when we left the area. As we worked, we used portable radiation instruments to survey how "hot" the samples in the area were. This would determine how long we could safely work with the sample or in that location.

If scientists wanted to use reference materials in the library, the librarian would look up our clearance in a card file to see if we were cleared to read the requested material. The authorities worked hard to compartmentalize our knowledge of what was going on. Even most scientists were kept in the dark about the Los Alamos progress on the bomb.

Even if I knew all the details about the nuclear bomb effort, I would have completely supported the idea to develop it. We all were involved in a total effort to defeat the Germans and Japanese, and we had to use any weapon that could be developed. The bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese was terrible, and we never forgot that event.

In 1960 I left Oak Ridge National Laboratory to become a physics professor at Emory and Henry College in Emory, Va. I retired from teaching in 1987.

By Clair Schersten '39, Oak Ridge, Tenn.

In March of 1944, I learned of a secret scientific project vital to the war effort. Larry Magnusson, my friend since childhood, was involved with the project at the University of Chicago. He could tell me only that I'd find the work highly interesting, and he suggested that I apply.

At that time I was at Augie completing a chemistry major I had discontinued to take some "pre-sem" courses. After two academic years in the Seminary and two years as an intern and "student pastor," I came to the conclusion I belonged instead where my natural bent and talent lay — in science and math.

Soon after an interview with the people in the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, I arrived in Knoxville, Tenn. There, in a small downtown office, I learned I would be working and living at a location 25 miles west, in Oak Ridge, on government-owned land. I rode on a shuttle to Clinton Laboratories (to be named Oak Ridge National Laboratory shortly after the war).

What I learned about the Project's magnitude from a young chemist, already on the payroll, who happened to be the only other passenger on the shuttle, was startling to say the least. Only 16 months after groundbreaking, thousands were already employed at three major laboratories on the site. The total population on the 90-square-mile Oak Ridge reservation was estimated at 60,000, many being families of construction workers living in "trailer camps" while completing work on the third massive plant. The three laboratory plants were located miles from each other and from "town-site." The town had stores, schools, cafeterias, a post office, recreation halls, two theaters, two bowling alleys, at least two dozen dormitories and already maybe 4,000 houses. More than half were "pre-fabs," but the others on permanent foundations, with many more being built.

But the most amazing information of the day came from the Clinton Laboratories' security officer. The objective at the lab, or X-10 as it was called, he said, was to produce a new element, plutonium, by the neutron bombardment of uranium metal in "the pile," as the graphite reactor was called. Plutonium is capable of fission-being split into smaller elements with the release of tremendous energy. He said an atomic bomb the size of the large glass ashtray on his desk could have the power of 20,000 tons of TNT! He told us this in a hushed tone and stressed the absolute secrecy of the project.

For the first nine months, I worked in the analytical control lab to determine the very small quantities, at least in the beginning, of plutonium produced. We also measured the total beta and gamma radiation in the samples.

The project was challenging and exciting because its goal was a way to put an end to the awful war. The work was equally challenging because it was in entirely new fields of nuclear physics and radiochemistry.

Exciting events also were happening in my personal life during my first months as a Tennessean. On June 30, 1944, Marion Mirfield '43 and I were married. Our first residence at Oak Ridge, for more than two months, was a dormitory room with a shared bathroom. We then moved into a one bedroom apartment in a residential neighborhood. In April 1946, we qualified to move into a two-bedroom house because we were expecting a baby. Carol '68 was our first child, followed by Tom '71 and Mark '74.

After WWII ended, the research and development program at the lab changed in focus and direction. It moved toward nuclear reactors for energy production and toward radio isotopes separation. I worked for a year on the separation of some radioactive fission products, and about three years in radiochemical process development. Then my interest and assignments shifted toward administration. From 1950 to 1961, I was the assistant to the director of the chemical technology division. Then I was transferred to Union Carbide's central research and development site in West Virginia, where I worked until retirement in 1983.

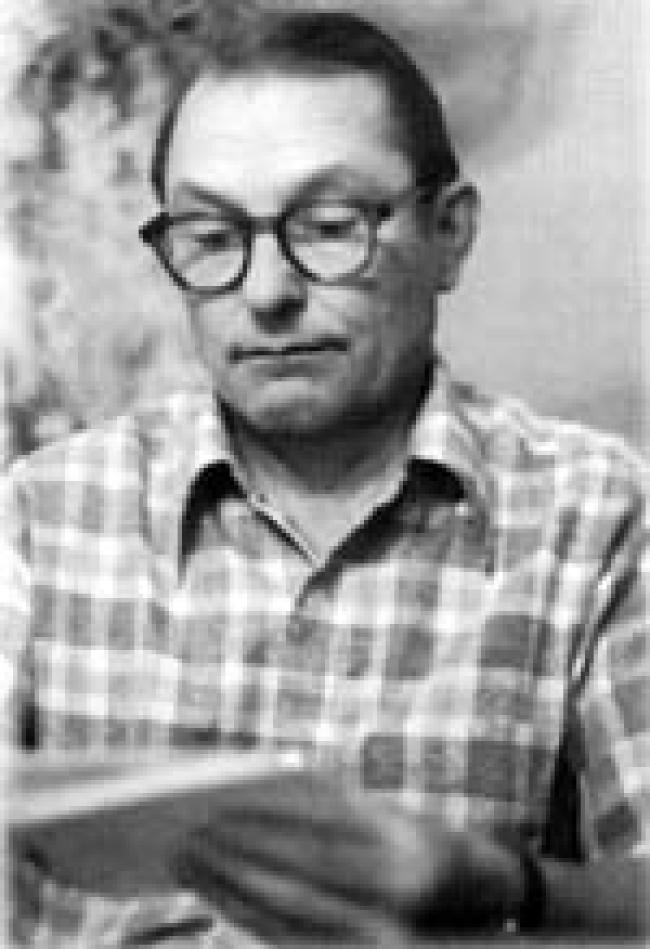

By the late Dr. Lawrence Magnusson '40, University of Chicago

The Rock Island unit of the Illinois National Guard was mustered into the U.S. Army in the fall of 1940. I was there but chose not to join my former comrades because I was near graduation and felt I could contribute more, if need be, in science than as a corporal in an artillery unit.

I remember hearing F.D.R.'s "Day of Infamy" and declaration of war on the radio in a shared office-lab in grad school in Ames, Iowa. A profoundly chilling moment.

In late spring of 1942, thanks to Civil Service, I found myself shoveling sulfur in a chemical warfare service plant in Huntsville, Ala. We made tons and tons of the nasty stuff-mustard gas and lewisite — in case the Nazis should revert to chemical warfare. Several workers were killed. I had a near death experience from sniffing what I believe was phosgene.

There was no science in Huntsville, and I got out as soon as I could. In 1943 I was picked up at an American Chemical Society meeting in Pittsburgh by a recruiter from the mysterious Manhattan Project. After arriving at the University of Chicago, I soon learned that a distinguished group of scientists was attempting to make a monstrous bomb based on nuclear energy. It was believed that scientists in Germany were working toward the same objective. The assembly of scientific talent associated with the Manhattan Project was awesome to me, a neophyte, Fermi, Conant, Condon, Szilard, Teller, Oppenheimer, the Compton brothers Karl and Arthur, Zachariasen. I met these people. In about a week I had ascended from hell to heaven in the scientific world.

Dr. Glenn Seaborg, who won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1951, gave me the job of isolating enough of the newly synthesized element 93, neptunium (Np), to study its chemical properties. This was important because Np-239 is the precursor of plutonium-239, the bomb ingredient used in the reactors at Hanford, Wash.

Our initial source of Np was uranium bombarded in accelerators, or cyclotrons, at Berkeley University and the University of Chicago. A co-worker and I were able to isolate a few micrograms of Np-237 to determine the half-life of the unstable element. Our determination, with a smidgen of the stuff, proved to be accurate to within one percent according to measurements made many years later. That made us feel good. Later, with milligram amounts isolated from reactor plutonium, we were able to study the chemistry of neptunium in detail.

At the war's end, Professor Seaborg invited me and some friends to go to Berkeley to complete graduate studies. So began another fascinating chapter in my life.

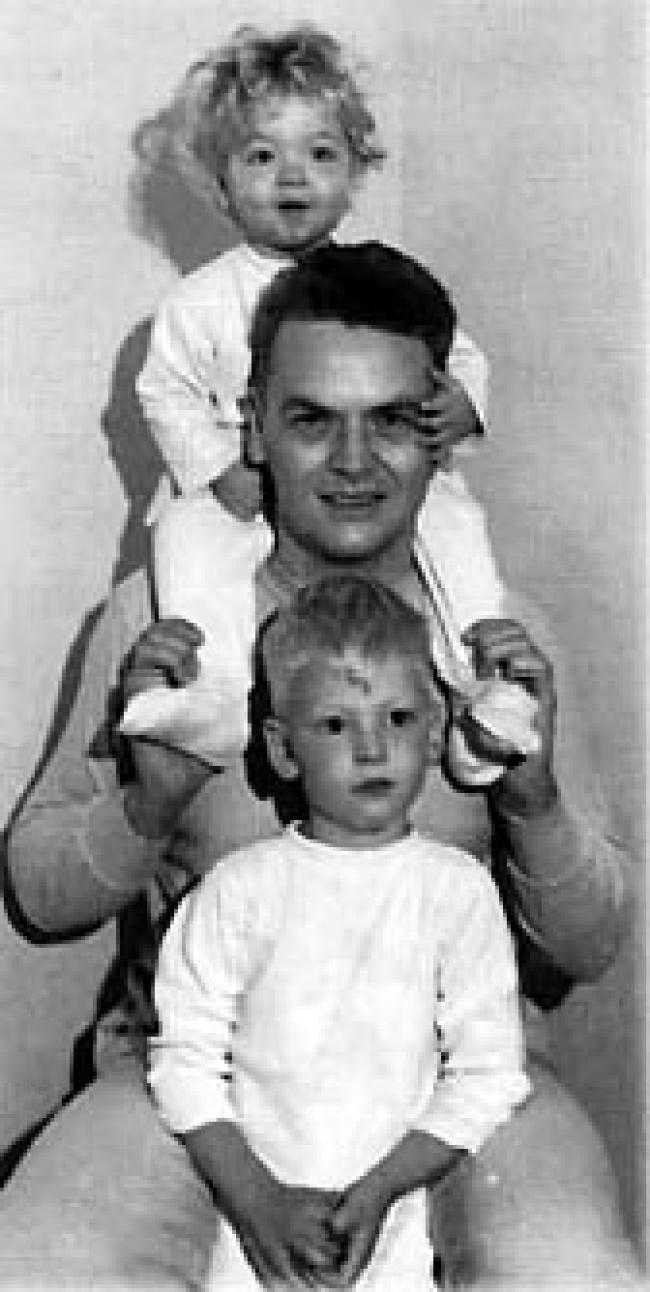

By Dr. C. Marcus Olson '32, University of Chicago

My academic research in X-ray spectroscopy and industrial experience in the separation of finely divided solids prompted an invitation for me to join the Manhattan Project. My association with Dr. Glenn Seaborg was not critical in the success of the Manhattan Project, but he gave me an honorable mention in his weighty book.

In reality, my contribution to the success of the Project was most modest. I participated in the research and production of plutonium synthesized in reactors called "atomic piles." It was a necessary task but I have a problem being proud of it. One does not take pride in meting out punishment.

As events turned out, the Allies guided by radar defeated the Japanese on the high seas, blowing their ships out of the water. My participation in the development of air-borne radar in 1942 — finding a feasible process for producing electronic grade silicon -- gives me greater comfort. Getting that equipment deployed even a day earlier may have allowed some airmen a chance to get home.

I must add that a substantial measure of credit is due to another Augustana graduate. Loraine Swanson '33 Olson. Along with our two small children, she followed me with tender loving care, having no idea whatever about the work or hazards to which we were exposed.

After WWII ended, I left my position at the Hanford site in Washington start to resume my peacetime research at DuPont.